See a Little Light Read online

Page 10

There was a hitch though. Spot had bought used recording tape because it was cheaper than fresh reels. The tape turned out to be the sixteen-track master from a TV broadcast by the Bee Gees, and it needed to be erased before use. The sixteen-track recording didn’t line up with the twenty-four-track machine, so Spot had to improvise a little spacing gimmick using pencils. This process added hours to the initial session, which left me drinking more “coffee,” some beer, and chomping even harder at the bit.

Since we typically recorded our basic tracks (drums, bass, rhythm guitar) in one take, we used the Byrds’ “Eight Miles High” as the warm-up track, not wanting to wear out any of the original songs. My vocal performance on that track was beyond intense though. It was straight from the primal core—like the wailing of an abandoned child or a stricken lone coyote howling on the side of the road. Little did I know that this version, which appeared on a single and preceded the album release by a few months, would set the stage for so much of the attention that Zen Arcade would eventually receive.

Most of the tracks were indeed first takes. We always preferred those because you’re not overanalyzing what you’re doing. We moved quickly through basic tracks, then on to guitar overdubs, vocals, keyboards, and percussion.

We established the general sequence of the album before we recorded. On side three, we created two piano interludes to bridge songs in unsympathetic keys. “Somewhere” was in D, and so in order to get to “Pink Turns to Blue,” which was in C-sharp minor, Grant and I constructed “One Step at a Time.” Similarly, we needed a musical bridge between “Newest Industry” (in F-sharp) and “Whatever” (in G). This time, I wrote a descending piano motif in F-sharp, but instead of using composition to move the listener’s brain up a semitone, we gradually increased the speed of the twenty-four-track machine while mixing the song to the stereo master. As the track plays, the gradual rise in pitch is barely noticeable, but listen to the first five seconds, then the last ten seconds, and the key change is surprisingly obvious.

The album was mixed in one forty-hour session. I suspect the main reason for this rather foolish move was that we had a show in Phoenix and we wanted to drive away with a finished version. Some of the mixes certainly suffered due to this marathon approach—there is no way anyone’s hearing can stay fresh enough to mix a double album in one forty-hour sitting.

* * *

I wrote a lot of the words to Zen Arcade in the back of what we affectionately called “the pimpmobile,” a tricked-out van done up with rust-colored shag carpeting and a collapsible purple velour platform bed. This was the second van that my father had driven the twelve hundred miles from Malone just so his son could travel safely with his bandmates.

Many nights, parked in front of SST while Grant and Greg were sleeping under a desk or in a corner of the office, I’d be writing beneath the dull dome light in the back of that van. I scribbled for hours and hours, filling notebook after notebook with uncertainty, anger, and self-hatred. Later I’d review what I’d written in the heat of the moment, then trim it down into two-and three-minute songs.

Right before I met Mike, I’d been hung up on a young guy in Minneapolis. He was beautiful and I fell for him instantly. We saw each other for a week, but it didn’t work out. I was angry, thinking I was never going to get a break. I ended up with a wonderful boyfriend in Mike, but at the time, I felt a lot of anger and frustration, mostly at myself. I’d let myself fall head over heels for this kid, even though he clearly wasn’t interested in trying to build on our week of young lust.

I had a lot of issues with my parents then. Since when hadn’t I? But not being open with them about my sexuality was one of the biggest. During a phone call in 1980, my father acknowledged, in a hostile way, that he thought I was a “fag.” In the same breath, he again threatened violence against my mother. Even from a distance, and despite the support he’d given me, he knew he could use this as a way to try to control everyone and everything.

My father was going to do what he was going to do, and my mother had made the choice to stay with him. I had to learn to separate myself from this dysfunctional family dynamic. That’s the life they made for themselves, but I couldn’t be part of it any longer. Maybe that was supposed to be the cinematic moment when the son rises up to the father, confronts and defeats him, and becomes his own man. I only remember thinking, You’re a crazy person, and I don’t have any more time for you. Boom.

A lot of this stuff—the blinding rage, the expression of youthful confusion, and the bumpy passage to adulthood—found its way to Zen Arcade. There’s a poetic irony to all of this: writing those words, crafting them into these fiery balls of uncertainty, preparing them for what I knew would be a momentous recording session—almost all done in the back of that van, yet another gift my dad gave to me.

* * *

The upbeat but cautionary “Something I Learned Today” was a not-so-vague LSD allegory that set the psychedelic tone for what was to follow. It was grabbing at images that were going by my life’s windshield: life in the van, the constant travel, my life on the road. Given that fact, “Chartered Trips” needs little explanation. “Broken Home, Broken Heart” was partly based on the fact that Greg’s parents were divorced, and partly informed by my own family situation. “Never Talking to You Again” is clearly one of Grant’s best songs.

A lot of side two is my blind rage and self-hatred, my failed relationships, and my confusing sex with love. That whole side was a blur while recording. It sounds like someone is being pounded into a gigantic pile of broken glass. Some of the words and ideas seem misguided now, but history has proven they’re made of a lasting substance. Gay people have always pegged “The Biggest Lie” as a gay song, and it is, seeing as it was informed by a sexual misadventure with a straight friend. It was about me hoping an awkward physical tumble would turn into something more, and it not happening.

Before I went in to record the vocals, especially for the songs on side two, I really tried to take myself back to the emotional place where I first experienced those things. It was like what prizefighters do before a match—they go into this dream state, hitting themselves and babbling to get psyched enough to perform beyond their capabilities. I did stuff like that before I went in to record. To be blunt, I was out of my fucking mind, barking at people and scaring the shit out of everybody. It worked. You can hear the results on the record, but I’m sure it took its toll on the people in the room, Grant, Greg, and Spot.

“Whatever” dealt with my battles with my family, but less through anger and more through resignation.

Mom and Dad, I’m sorry

Mom and Dad, don’t worry

I’m not the son you wanted, but what did you expect?

I’ve made my world of happiness to combat your neglect.

Grant’s song “Turn On the News” made the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame’s list of the “500 Songs that Shaped Rock and Roll,” a great achievement for a song that I thought was a bit of a throwaway. In hindsight, though, the song’s lightness and hope was the balance for the heaviness and despair that I so ably and amply dealt.

Side four, the thirteen-minute “Reoccurring Dreams,” was certainly a stroke of luck. We were just jamming, improvising, playing the signature riff over and over again, and Spot reached over and turned on the two-track and happened to capture a really heady riff, with everyone just going off on alternating waves of tension and release. If not for that, we might have been short one side of a double album.

We recorded two additional songs of mine that didn’t make the album, partly because they didn’t fit into the narrative and partly because they simply weren’t up to snuff, as well as that scorching cover version of “Eight Miles High.” We could have used those instead of “Reoccurring Dreams,” but it wouldn’t have been quite the same, or as good, as the finished body of work that people know as Zen Arcade.

* * *

Zen Arcade is regarded as this momentous work that requires deep explanation. Th

e fact was, we were rehearsing and touring nonstop, not spending a lot of time thinking about it. We were doing it. We were living it. It was a visceral statement. It felt right.

It’s a very good record, but it’s the sum total of the experience, of that moment, that grabbed people. Now I hesitate to say this, but here goes: Zen Arcade means a whole lot more to others than it does to me. I began to outgrow and move beyond those feelings almost at the moment I documented them, but the fact that they resonate so deeply with my audience, the critics, and generations of fellow musicians—there is the reward.

CHAPTER 8

We finished up the October 1983 tour with stops in Phoenix and Denver. In Phoenix we played a show with SST label mates the Meat Puppets at Madison Square Garden, a venue used primarily for local pro wrestling and boxing events. The ring was in the middle of the building, wrapped on three sides by a fifteen-foot-high cyclone fence, and served as the bouncy and unstable stage for music shows. Kids climbed the cage while bands thrashed through their sets. After the show, I recall riding around the back roads of Phoenix in the Meat Puppets’ van while they chucked urine-filled mason jars out the windows.

In December we added a fourth member to the touring entourage. We’d met Lou Giordano, a lanky, brainy fellow with a wonderfully dry sense of humor, earlier in the year in Boston when we needed a last-minute soundman. Lou joined us for a short East Coast tour. At Lou’s first gig with the band at Love Hall in Philadelphia, a kid fell from twenty feet above the stage and landed like a sack of potatoes in front of Grant’s drum kit. The kid was in rough shape but made it off the stage alive. Welcome to our world, Lou.

Now that the touring party had grown to four, it was time to start getting motel rooms on a nightly basis. The band was traveling hard and making better money, and we needed more peace and quiet, not to mention sleep. Lou roomed with Greg and Grant roomed with me. I wasn’t a neat freak by any stretch of the imagination, but I liked some semblance of orderliness. By contrast, upon opening the motel room door, Grant would toss his well-worn, wildly overstuffed hard-shell suitcase onto a bed, and it would typically spring open on its own, spraying its contents all over. It was comical, the exploding suitcase. When it was time for Grant to call home, I would retire to a long, hot shower, thereby giving him all the privacy he needed. Grant would always return the courtesy. We were decent roommates.

We toured sporadically in the first half of 1984, knowing we would work hard in July, when Zen Arcade was finally to be released. There were a handful of highlights, including two dates in March in Boston with REM. They asked us to open for them at the Harvard Field House, and the following evening, despite their ability to sell way more tickets than us, they supported us at the Rat, a smaller Boston punk club.

Starting in mid 1983, we became incredibly prolific and were always anxious to try out new songs, so we tended to play new material on tour, as it was written. This often meant we were playing music from albums that hadn’t been released or even recorded yet, instead of the album we were promoting. The conventional wisdom is, you flog your latest album, but we didn’t care. We weren’t there only to sell records. That’s just another thing that set us apart from other bands.

In April 1984 SST released the Eight Miles High single, which gained some attention from both the US and UK press, and by May we were already test-driving several selections from what would be the follow-up to Zen Arcade, which hadn’t even been released yet.

In Norman, Oklahoma, just for the hell of it, we played a version of “Reoccurring Dreams” that lasted almost an hour; the last forty-five minutes, I played one E chord on my guitar. It was funny, watching people go from smiling to “OK, we get it” to “now we’re pissed” to then being just plain stunned. In Austin we played in the basement of Voltaire’s bookstore; someone let off a stink bomb in the packed and airless basement, which not only ruined the show, but could have ended in tragedy. In June we played the Electric Banana in Pittsburgh, a club built precariously on the edge of a steep cliff. We arrived early and fell asleep on the vacant club stage, only to be awakened by the son of the club owner shooting at us with a pellet gun. After a sound check at the Rat in Boston, a young fellow showed up in a surgical halo, informing us that he had broken his neck while stage diving at our previous Boston gig.

On June 23 we played our very first show at the great Hoboken club Maxwell’s, which soon became a standard stop on the indie rock circuit. The club owner was a very gregarious fellow named Steve Fallon. Steve’s gaydar went off on me immediately, and I finally had somebody in a big city who knew gay, who knew I was gay, and who I could learn from. Maxwell’s was gay-friendly, but it wasn’t a gay bar. It was just a scene that happened to have gay people in it.

We kept playing shows, but July 1984 was a momentous month for two reasons: the long-awaited (and long-delayed) release of Zen Arcade and the recording sessions for the follow-up album.

Nine months was a long time for a record to sit, especially for SST, but apparently they wanted to release our album on the same day as the Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime, the double album they decided to make when they heard we were making one. (The Minutemen could have made a triple if they wanted to; they were that prolific.)

Zen Arcade comes out and right away there’s a lot of critical acclaim. I felt validated. I’d been telling people that we were going to do something bigger than ever, and lo and behold we did. But even more than validation, I felt relief—relief that we actually delivered on all my hubris.

There was one problem though: no one could find Zen Arcade in stores. We got to the record-signing party at an indie music shop in Columbus, Ohio, and there were no records. So we had to go down to the local print shop and hastily design flyers so we’d have something to sign for people. Turned out SST had been worried about printing up more than five thousand copies or so—anything beyond that was uncharted territory for them—because if that pressing didn’t sell out, they’d have to eat the cost. But the initial pressing sold out quickly and, in reality, the album wasn’t widely available until September, when SST was able to do another pressing. We had warned them that this was going to be an important record and that they needed to press up more copies than usual. They were not at all prepared for what was happening.

It was a discouraging situation. We were out there trying to sell the record, and there were no records for people to buy. Turned out SST wasn’t quite the utopia people thought it was. That was the first crack in the bond between Hüsker Dü and SST.

We were being the good soldiers, doing as we were told. The SST deal gave Spot 25 percent of the band’s artist royalties, which was normal for SST bands. We understood that when we signed the contract. What we didn’t understand was how music publishing worked, and how individual songwriters were entitled to mechanical royalties. Before Zen Arcade, Ginn had control of our publishing through his Cesstone Music. We complained, got our publishing back, and divvied up the songwriting credits through our own entity, Reflex Music. Everything was now in accordance with standard music industry practices.

But at the same time, we were also deferring our royalties from SST so the label could cope with cash flow problems. Still, SST somehow had enough money to release no less than four Black Flag albums in 1984.

Months earlier we informed SST that we were going to record our next album in Minneapolis. Mixing Zen Arcade in one forty-hour session makes for a great story, but let’s face it, it wasn’t ideal. We wanted to spend more time making this next album and have more control over the recording environment. And while sleeping in the van or underneath Rollins’s desk was oddly romantic, we also thought it might be nice to make an album while sleeping in our own beds each night. Also, I wanted more time at home to further my relationship with Mike.

Making a life with Mike gave me some sense of safety and stability. But it was also a challenge for me, this being the first time I had someone to talk with about my thoughts. I was only twenty-three and still had some lear

ning to do, especially when it came to love and relationships. The dynamics of our families of origin are easy to emulate and hard to erase. The less flattering aspects always seem to resurface when times are tough, or when one or both people are living in an altered state.

Mike and I were drinking a lot, but when we were together, I was a happy drunk. When I was working though, I’m certain there were moments when I was tough to be around. Some people who were close to the band circa 1984 have portrayed me as dour, overbearing, even baleful. I don’t doubt those descriptions one bit—I’ll leave it to others to fill in the ugly blanks.

Steve Fjelstad had coproduced and/or engineered all the Replacements albums, and he offered to help us with our Minneapolis sessions as engineer. We booked time at Nicollet Studios, an old vaudeville theater turned recording studio complex on Nicollet Avenue, near Twenty-Sixth Street.

Spot came to town in the role of coproducer. The first day, Spot came in, sat down behind the recording console, and said, “Something’s wrong here. We’re going to need to move this console three inches—it’s in the wrong place.” It was a ridiculous request. He couldn’t move his chair three inches? It was a power move, designed to establish some sense of dominance over the rest of us. Without making an issue, we all lifted this fucking-huge board that’s been in the exact place for a long time, and moved it three inches.

New Day Rising was a very different album from Zen Arcade. They were composed only a matter of months apart, but when I look back, it seems like years. Before New Day Rising, it was words floating around in notebooks, and me sweeping them up and gathering them all together in my hands like they were snowballs or fastballs, spitting on them, and throwing these words at the listener. The songs were outbursts of confusion, dealing almost exclusively with problems, and rarely offered answers. But the new songs, and their imagery, were different—they addressed time, the transitory nature of emotions, and the passing of seasons.

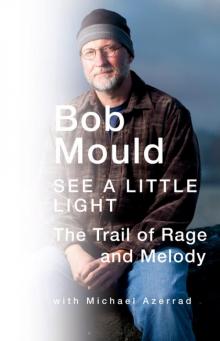

See a Little Light

See a Little Light